By Dr. Krystal Redman, DrPH, MHA (they/she)

The largest breast cancer symposium in the world, the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), is dominated by researchers and clinical practitioners eager to present and discuss the latest research and practices. In this space, the fast paced environment, medical jargon, and complex science can be hard to understand. Yet, patients are asked to trust the science, a common theme weaved throughout the four-day symposium, however oftentimes the patient voice is not centered in these spaces. Over the years, there has been a growing presence of patient advocates who attend this symposium, but there is so much more that needs to be done in the field of breast cancer research.

The deep distrust of science and healthcare among people of color is like a wound that has festered in the dark for so long and has now brought to the limelight in the wake of COVID-19. Numerous approaches have been discussed for addressing this distrust, including the inclusion of patient advocates in clinical research. Patient advocates are those who have breast cancer, those living with breast cancer, their caregivers, or others that are affected by breast cancer. Patient advocates can be powerful players in building trust in medical interventions, even during the clinical research phase. However, there are right and wrong ways to go about including them.

To start with, there is no inclusion without mutual trust, and mutual trust is built on transparency, an acknowledgement of how clinical research has been conducted in the past, and a willful intention to disrupt those past approaches in favor of a model that is truly patient-centered. Second, inclusion must be accompanied by engagement. Engagement will allow the centering of patient advocates’ lived experiences and allow them more opportunities to get involved in research and studies that can aid in addressing and ending breast cancer.

Most discussions regarding the roles of patient advocates are premised on the notion that the data-driven, evidence-based, scientific viewpoint is complemented by a non-scientific and passionate viewpoint from patient advocates. At best, this assumption is limited, and at worst, it is grossly inaccurate. Patient advocates absolutely bring a scientific viewpoint to the table. The lived experiences of these advocates constitute real-world data – qualitative data – in addition to a deep interest and motivation in addressing and eliminating breast cancer. To put it differently, healthcare workers and researchers bring perception, while patient advocates bring perspective.

Engagement of patient advocates in clinical research and breast cancer drug development requires building trust in science. Engagement must be holistic. Patient advocates should not be treated as a means to an end- they are more than participants in a study, they are people and should be treated as so . Such an approach can only further alienate them and stoke the fires of distrust. Rather than wait until the trial recruitment phase or even later, as is often the case, engagement of patient advocates should begin during the planning phase, when a grant application is still being considered. Engaging patient grassroots advocates, those who haven’t been hand-picked and groomed by pharmaceutical companies, throughout the entire drug development process will build trust and a sense of ownership. This level of engagement will entail keeping the patient advocates fully informed, including grant approval or denial, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) applications and outcomes, etc. To learn more about the lack of and critical need for an open-door of communication between patients and the FDA in read a blog written by BCAction member, Marie Garlock.

Not only should patient advocates be engaged early and often in the drug development process, but equally important, before approaching them researchers must establish why they want to include them, what type of patients are needed, and what their roles, responsibilities, and expectations will be. When and how communication will happen between the researchers and patient advocates must be decided, to avoid confusion and misunderstanding. In selecting patient advocates, fairness and representation are important considerations. Language, culture, race/ethnicity, gender, age, and disability, are some factors to keep in mind. As a rule, patient advocates should be offered compensation for their time. They are collaborators and their compensation should be built into the grant equitably.

Inequities in the healthcare system have been a painful and long-standing reality for people of color. Care that is not equitable across people and communities is not care. To achieve real and lasting gains in health equity, there must be trust in the systems that provide care. In the words of the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium “Trust in Science“ session Moderator, Maimah Karmo (founder and CEO of the Tigerlily Foundation), says, “the social contract that binds us all is trust.” Trust in science and healthcare systems is best built by listening to the people affected, learning about their lived experiences, and asking them how you can use your privilege to empower patients and eliminate disparities in the healthcare system.

Breast cancer disproportionately affects Black women, especially when it comes to age at diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, and how likely they are to die from it. The matter is made even worse by the limited information we have about metastatic breast cancer–which also disproportionately affects Black women. Despite being the worst affected population, the participation of Black women remains under-represented in clinical trials and there is a persistent racial gap in funding for breast cancer research. Efforts to remedy these disparities have not been very successful to date, as the same communities continue to have poor outcomes year after year. Disparities in health outcomes are often blamed on poor compliance or low socioeconomic status. However, to be effective, attempts to eliminate racial disparities in breast cancer must focus on systemic anomalies, not on individuals.

Research shows a persistent mortality gap between Black women and white women. While white women are more likely to get a breast cancer diagnosis, Black women are more likely to be diagnosed at an earlier age, at a later stage of cancer, and with more aggressive forms of the disease. Black and Indigenous People of Color are also less likely to receive the standards of care recommended for the stage of cancer with which they were diagnosed. While white women are more likely to be told their diagnosis in the physician’s office, Black and Indigenous People of Color are more likely to hear it over the phone. A white woman is more likely to receive a biopsy within 24-48 hours of biopsy while a Black woman gets told to “let’s see how this progresses.” These disparities result in Black women having a 40% higher death rate from breast cancer than their white counterparts. Besides disparities in access to care, false beliefs about biological differences between Black and white people continue to inform medical judgments and may negatively impact treatment choices. For example, white medical students, residents, and lay people have been shown to believe that the bodies of Black people are naturally stronger than those of white people. These mistaken notions and mental biases can be problematic and may cause delays in initiation of treatment for Black women with breast cancer.

Health inequities continue to be propagated by deep-seated distrust of the healthcare system. Acknowledgement of the distrust is a necessary first step in ensuring equal access to care. White clinicians, researchers, and leaders in healthcare must start by addressing their privilege, and how they could have perpetuated and/or benefited from inequitable practices and/or systemic racism in the course of their work. Whether or not there was malicious intent is beside the point. Black people continue to suffer harm and those responsible must hold themselves accountable, regardless of intent.

Surface-level approaches to fixing disparities, such as hiring more Black and Indigenous People of Color are not enough. A genuine and transparent investigation of the systemic origins of racism and health disparities is needed. Such an investigation will invariably require a dismantling of those policies and structures that perpetuated injustice and a rebuilding, with deliberate emphasis on equity.

Increasing representations of BIPOC folx in medical schools and clinical programs is great, but not quite enough. Efforts to address health disparities must reach to the very foundations of health care, even up to the restructuring of medical school curriculums. These efforts will need to go beyond committees made up of BIPOC folx, to foster equitable access to equitable care in a setting of cultural humility.We need a concerted effort to address racism, racial disparities in healthcare, and mistreatment of patients of color, through genuine intention and accountability.

The building of trust is a long-term goal and can only be achieved through consistency in truth-telling, honesty, listening, decentering of privilege, naming and addressing inequitable power dynamics, and much more. When longstanding institutions are dismantled and restructured, with the new goal of being for all people, when the dynamics of power are revisited and reorganized with a view to ensuring fairness, then we can begin to build trust.

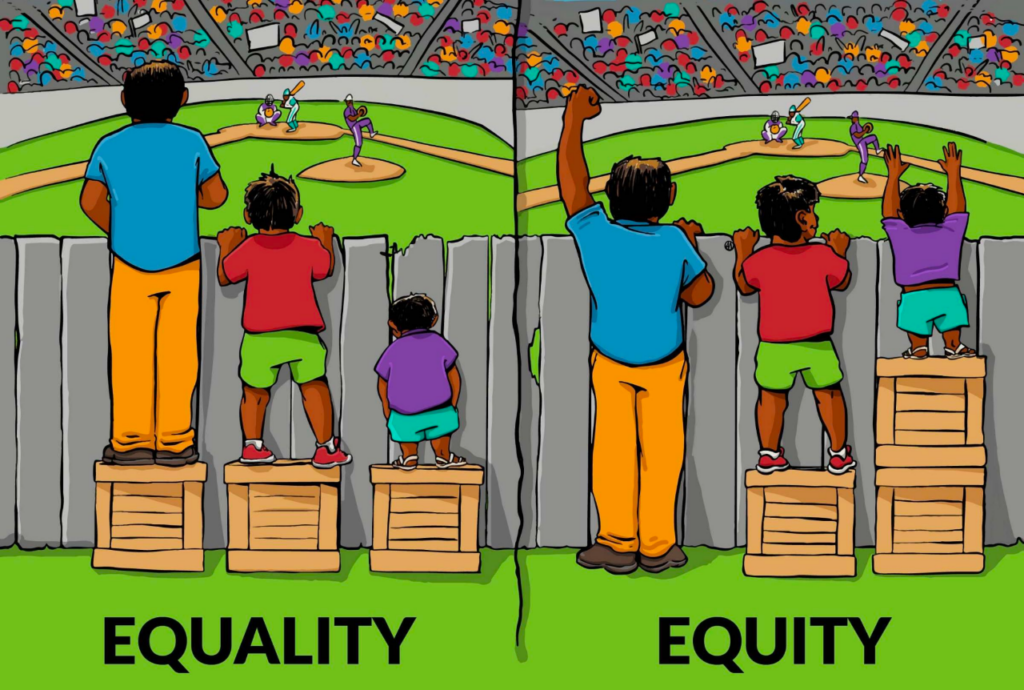

by IISC, January 13, 2016, Illustrating Equality VS Equity

The above graphic is a very familiar illustration of “equity vs. equality”.

At first glance, this seems like a clear illustration of ensuring that people get the things they need in order to thrive. Seems simple enough, right? Well, not really. Applied to the context of equity in patient research and care, the illustration would suggest that all we need to do is ensure that each patient has what they need to survive and be included.

I challenge you to take a deeper look at this picture. This is an image that we at BCAction have taken time to criticize deeply. We have asked ourselves, “why is there a fence creating a barrier in the first place?,” “why aren’t these folks allowed in the stadium?,” “why are additional resources not provided to those in the picture?” (as you can see, there are 3 boxes in the “Equality” section of the illustration, and still 3 boxes in the “Equity” portion; there were no additional boxes or “resources” brought into the picture). There are so many other questions and points we could raise here, but the bigger point is that “equity” requires the dismantling of systemic barriers to equitable access to care, demands access to equitable resources beyond what has been scarcely allocated, and challenges those in power to decenter their privilege, in order to truly achieve health justice, which allows those with the furthest relationships to power to not just survive, but to thrive!

Clinical trials of breast cancer drugs provide hope of better treatments. However, when it comes to health care, treatments are often not “one size fits all.” This makes the disproportionate representation of Black and Indigenous People of Color in clinical trials problematic. Their poor representation in clinical trials often derives from the fact that BIPOC communities are not actively recruited into clinical trials by their physicians and they are more likely to be treated at smaller centers with limited access to clinical trials.

To facilitate the participation of Black and Indigenous People of Color in clinical trials, large academic centers and centers of excellence for cancer treatment need to share resources with smaller, community clinics. Not only should physicians in these clinics be able to offer clinical trial participation to patients, they should also be able to provide adequate support and follow-up on patients’ care. Cross-sector partnerships and collaborations will go a long way to cultivate relationships and address non-medical needs that serve as barriers to engagement in clinical trials and medical care.

Accountability in clinical trials is a must. Funders must hold researchers accountable when they don’t live up to the promise of inclusion and engagement of Black and Indigenous People of Color. Beyond closing gaps in research funding, funders should invest equally in community-based organizations that serve as bridges to connect patients’ communities to researchers and care providers. Disproportionate allocations of grant funds to community partners and patient advocacy groups only serves to perpetuate a lack of diversity in clinical trials. These organizations need resources in their work to reduce and eliminate barriers to engagement, and should also be recognized and paid for their time, labor, and contributions to science. Clinical trials should earmark funds specifically for targeting Black and Indigenous People of Color, increase their participation and engagement. Similarly, during the grant application process, researchers should be required to demonstrate how they will engage communities of Black and Indigenous People of Color, and should be held accountable if they do not live up to that expectation. Without accountability, change will never happen.