A growing body of evidence from experimental, body burden and ecological research indicates that there is a connection between environmental factors and breast cancer. There are over 85,000 synthetic chemicals on the market today, from preservatives in our lipstick to flame retardants in our sofas, from plasticizers in our water bottles to pesticides on our fruits and vegetables. The U.S. government has no adequate chemical regulation policy, therefore companies are allowed to manufacture and use chemicals without ever establishing their safety. As the use of chemicals has risen in the U.S. and other industrialized countries, so have rates of breast and other cancers.

Here are some key facts you should know about the environment and breast cancer:

Not enough research is being done on environmental links to breast cancer and other cancers and BCA is working to change this. As we pursue the research that will lead to even more definitive answers, we can and should reduce our exposure to substances we believe cause cancer by using the precautionary principle of public health.

The precautionary principle is the common sense idea that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Now more than ever, we need to take precaution to protect our health. There are over 85,000 synthetic chemicals on the market today, from preservatives in our lipstick to flame retardants in our sofas, from plasticizers in our water bottles to pesticides on our fruits and vegetables. The U.S. government has no adequate chemical regulation policy, therefore companies are allowed to manufacture and use chemicals without ever establishing their safety. When government does step in to regulate chemicals, it uses a “risk management” model that asks, “How much harm is allowable?” For example, a local recreation and parks manager might ask, “How much arsenic is okay to allow in arsenic-treated wood playground equipment?” The precautionary principle instead asks, “How little harm is possible?” Following a precautionary principle approach, the manager would ask, “What are the alternatives to using arsenic-treated wood?” and “Do we need to use arsenic treated wood at all?” We can use the precautionary principle to reduce and eliminate our exposure to chemicals we know or suspect cause harm.

The main components of the precautionary principle are:

The precautionary principle is being used by communities and governments around the world to protect human health and the environment. BCA, as a member of the Bay Area Working Group on the Precautionary Principle, is working with Bay Area governments to encourage the adoption and implementation of the precautionary principle. So far, San Francisco and Berkeley have recognized the wisdom of “better safe than sorry” when it comes to chemicals and the public’s health by passing precautionary principle legislation.

You can use the precautionary principle in your home by switching to nontoxic cleaning products and safer body care products, and by shopping organic. Remember, just because a product is on the store shelves doesn’t mean it’s safe.

As we push for more and better data, we continue to demand that lawmakers and industry abide by the precautionary principle by acting now, on the basis of the weight of the evidence that already exists, to reduce and eliminate our exposure to chemicals we know or suspect cause breast cancer and other chronic diseases.

Environmental health tracking is one way for us to gather more information about diseases and how they may be linked to what we’re exposed to in our air, water, and homes in order to take action to protect our health. Currently, we have very little data on exposures to environmental hazards and the health effects that may be related to those exposures. The chemical industry and polluters get off clean by saying “no data means no problem.” But when we consider the small but growing amount of evidence linking diseases like cancer, asthma, and Alzheimer’s to toxic chemical exposure, we know that “no data” really means that the problems just haven’t been adequately studied.

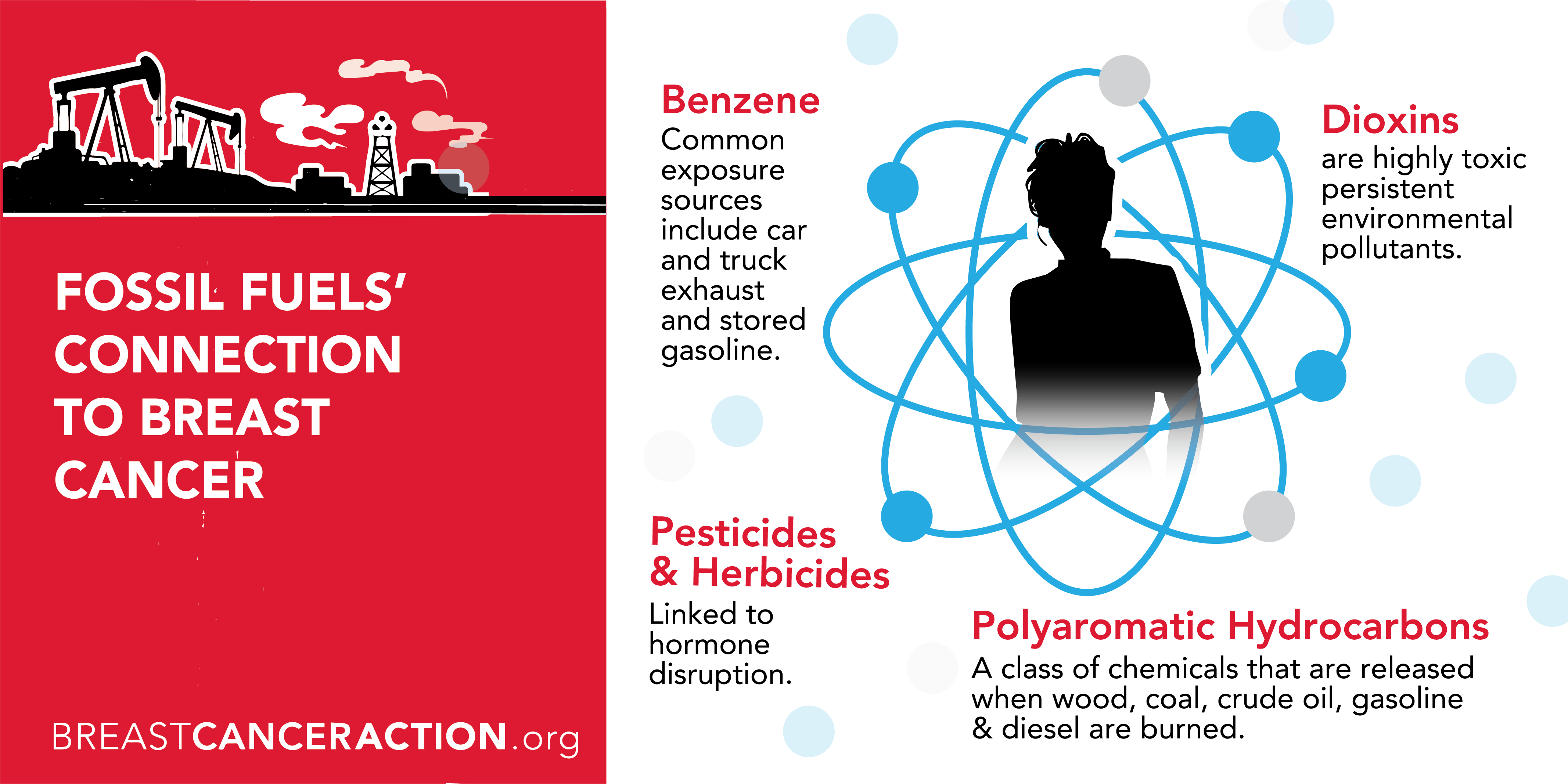

Environmental health tracking is one way to help bring those problems to light. In 2003, Congress appropriated $28 million to begin the development of a nationwide network to track when and where breast cancer and other chronic diseases occur, along with the presence of relevant environmental factors such as exposure to PCBs, dioxin, pesticides, and other pollutants. This data will hopefully help us better understand the links between diseases and environmental hazards in order to take action to protect public health.

A national system of environmental health tracking would:

Thanks to the 1986 Federal Emergency Planning Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA), industries have to reveal the amounts they release of more than 600 designated toxic chemicals. The Environmental Protection Agency posts the industry data in the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI). You can use the links below to search for information about the chemicals being released in your neighborhood and community. To learn more about the connection between chemicals and breast cancer, read The State of the Evidence.

Keep in mind that the 600 chemicals that must be reported under the Right-to-Know Act represent only a small fraction of the over 85,000 chemicals on the market today. As we demand our right to know more about the chemicals we’re exposed to and their health affects, we can use the precautionary principle of public health to reduce and eliminate our exposure to toxic chemicals.

Trade Secrets: A Moyers Report: A collection of links that serve as a guide to information available under right-to-know laws and other important information on Bill Moyers’s investigation of how the chemical industry has withheld vital details on the safety of chemicals from workers, the government, and the public.

Like many other questions about chemicals and human health, there is a lack of scientific data on the issue of plastics and the microwave. What we do know is that a number of plasticizers, or compounds added to plastics to make them soft, mimic the hormone estrogen when they’re ingested into the human body. Estrogen is a hormone closely related to the development of breast cancer. We also know that these compounds — DEHA (diethylhexyladepate), phthalates, and bisphenol-A — can migrate from plastics to food when heated to microwave temperatures, especially foods with a high fat, oil, or sugar content. The Food and Drug Administration and the American Plastics Council state that it’s still safe to use plastic in the microwave because there is no evidence that the small amounts of these chemicals being ingested is harmful. But lack of evidence does not equal lack of harm. Studies that test the effects of exposure from microwaved plastics do not take into account that we’re exposed to these chemicals through many other mediums and that they can accumulate in our bodies. Dioxin, a known carcinogen, is also used in some plastics and plastic wrap and is often included in the microwave debate. Dioxin is released when plastics are incinerated, but there’s no evidence that it leaches out at microwave temperatures. It’s best to abide by the precautionary principle and reach for safe alternatives, like ceramic or glass cookware, when you’re using the microwave.

A study published in early 2004 gave us new insight on the possible link between a whole host of body-care products, like antiperspirants, and breast cancer. The study, conducted by Dr. Philippa Darbre, found parabens — a chemical preservative commonly used in cosmetics and body-care products — in samples of breast cancer tumors. Although the study was quite small, looking at only 20 tumors, it tells us for the first time that parabens can in fact be absorbed through the skin from frequently applied products such as antiperspirants and creams, and can persist and accumulate in breast tissue in their original form.

Parabens are one of a number of chemicals that we’re exposed to in day-to-day products; they mimic estrogen, a hormone closely linked to the development of breast cancer. This study highlights the need for more research on the health effects of hormone-disrupting chemicals and our need to take precautionary action to eliminate our exposure to these potentially dangerous chemicals.

Parabens don’t belong in our body-care products or in our bodies. BCA has called on Avon, Revlon, Estée Lauder, and Mary Kay — cosmetic companies with pink-ribbon breast cancer campaigns — to remove parabens and phthalates (another hormone-disrupting chemical) from their products. We urge these companies to make good on their claim to be leaders in the fight against breast cancer. After all, corporate conscience belongs in a company’s products, not just in its marketing.

According to the Women’s CARE (Contraceptive and Reproductive Experiences) study, published in June 2002, using birth control pills doesn’t appear to increase a woman’s risk of getting breast cancer. The scope of the study didn’t include women under 35 or risks associated with the growing use of oral contraceptives by women over 40. Other studies have reached the same conclusion but have found that women with a strong family history of breast cancer are at increased risk if they started using oral contraceptives before 1975. Before 1975 the pills contained a much higher dose of estrogen than they do now. A recent Canadian study also found that women with the BRCA1 gene mutation showed an increased risk of early onset of breast cancer if they started taking the pills before 1975, before age 30, or for more than five years. Remember that genetic mutations account for less than 10 percent of all breast cancer cases.

Both estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) and hormone replacement therapy (HRT), combining estrogen and progestin, have been shown to significantly increase breast cancer risk. A meta-analysis of studies on ERT shows that women who use it for five or more years increase their risk of breast cancer by about 35 percent. The risk lasts as long as a woman takes hormones but disappears within five years after she stops hormone use. Studies on HRT demonstrate that the use of progestins increases breast cancer risk beyond that of ERT taken alone. As with ERT, risk seems to increase on HRT after five years. After that, the risk increases slightly with each additional year on HRT.

Bio-identical hormone therapies (BHT) have been promoted as an alternative treatment to traditional hormone therapy* (HT) for menopause. They are marketed as “natural” pills, creams, or gels that can be compounded — tailored to an individual’s specific needs — on the basis of saliva or urine tests. Ads claim effectiveness without the side effects of HT, which has been shown to significantly increase breast cancer risk.

Despite claims that BHT is safe, no one knows if this is true. There have been no large long-term studies of the side effects of BHT on the same scale as the National Institute of Health’s Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study, which looked at HT.

There are no BHT drugs which have met the FDA’s standards for safety and effectiveness. “Bio-identical” implies that the drugs are identical to hormones a body produces on its own, but this is merely a marketing term. The hormones are derived from pregnant mare’s urine (which is also used in HT) or plants and then manufactured in labs. Some BHT contains the hormone estriol, which has never been approved by the FDA for any drug.

The claims that BHT is safer and more effective are not based on credible scientific research, so we don’t know how they compare to HT. We do know that they are currently unregulated and that the FDA sent warning letters to manufacturers for violating federal law by making false claims about BHT.

Like HT, BHT may provide relief from menopausal discomfort and may pose the same health risks as any hormonal therapy, but BHT lacks regulation and evidence. While we do think women should have more options, BCA believes there must be evidence of safety and effectiveness for any hormonal treatment, whether it is a pharmaceutical or a “natural” product. Until more information about BHT becomes available, women will have to weigh the benefits of the product against the relatively small amount of research on its side effects.

To learn more about bio-identical hormone therapy, visit:

*Hormone therapy (HT) is also referred to as hormone replacement therapy (HRT). BCA uses the term “hormone therapy” instead of “hormone replacement therapy,” because the latter suggests that menopause is an illness that requires treatment by replacing the hormones that naturally decline during this time.

The question of a connection between fertility drugs and breast cancer is a very complicated one. To begin with, most women taking fertility drugs are over 30 and haven’t had a child yet. These factors together already increase their risk of breast cancer.

One widely used fertility drug, Clomid, works by causing a woman to hyperovulate, to pump out more of the appropriate hormones for stimulating egg development. Data now available suggest that Clomid increases the risk of ovarian cancer, since more frequent ovulation increases your chances of getting ovarian cancer.

However, the connection isn’t clear for breast cancer. In theory, these drugs and the hormones they contain, might add a promoter effect — stimulating the development of precancerous cells that are present. A lot of evidence shows that the amount of estrogen in a woman’s body increases breast cancer risk by promoting breast cancer growth. (For more on this, search our website, using the keyword “estrogen.”)

According to a couple of large recent studies, overall history of infertility drug use was not associated with increased breast cancer risk, but we need to do more research. We don’t know the relationship of these drugs to breast cancer, but it’s likely that they have some effect, since DES — a drug given to women from 1938 to 1971 to prevent miscarriage — and other hormones do. There are many questions that still need to be answered, and it may be many years until we understand the effects of these drugs on breast cancer risk.

Not enough research is being done on environmental links to breast cancer and other cancers, and BCA is working to change this. As we pursue the research that will lead to even more definitive answers, we can and should reduce our exposure to substances we believe cause cancer by using the precautionary principle of public health.