Breast cancer is not one disease. It’s a complex group of diseases that occurs in an environmentally complex world. It is second only to skin cancer in its rate of occurrence in women, and second to lung cancer in mortality rates for women. Each year, nearly 300,000 people are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer. Over half of those diagnosed with breast cancer in the United States have no known risk factors, and family history accounts for only around 10 percent of breast cancer diagnoses. A large and growing body of research suggests that toxic chemicals are causing an increase in our risk of developing the disease.

There are tremendous gaps that still exist in our understanding of the causes breast cancer. Despite better treatments and increased access for many, 40,000 still die from the disease each year. A woman is diagnosed with breast cancer every two minutes. In the 1960s, a woman’s lifetime risk for breast cancer was 1 in 20. Today it is 1 in 8.

Breast Cancer Action is committed to reducing our involuntary exposures to toxins in the environment that are linked with breast cancer. We do this important work because we are far from understanding the causes and risk factors of breast cancer, despite the billions of dollars and many decades spent on breast cancer research.

Back in 2010 the President’s Cancer Panel reported, “The burgeoning number and complexity of known or suspected environmental carcinogens compel us to act to protect public health… A precautionary, prevention-oriented approach should replace current reactionary approaches to environmental contaminants in which human harm must be proven before action is taken to reduce or eliminate exposure.”

In 2012, a report from the Institute of Medicine stated that “… it may be prudent to avoid or minimize exposure because the available evidence suggests biological plausibility for exposure to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, or there is suggestive evidence from epidemiology, or both.”

In 2013, the Interagency Breast Cancer and Environmental Research Coordinating Committee concluded, “By urgently pursuing research, research translation, and communication on the role of the environment in breast cancer, we have the potential to prevent a substantial number of new cases of this disease in the 21st century.”

By 2018, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences concluded that “Most experts agree that breast cancer is caused by a combination of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors.”

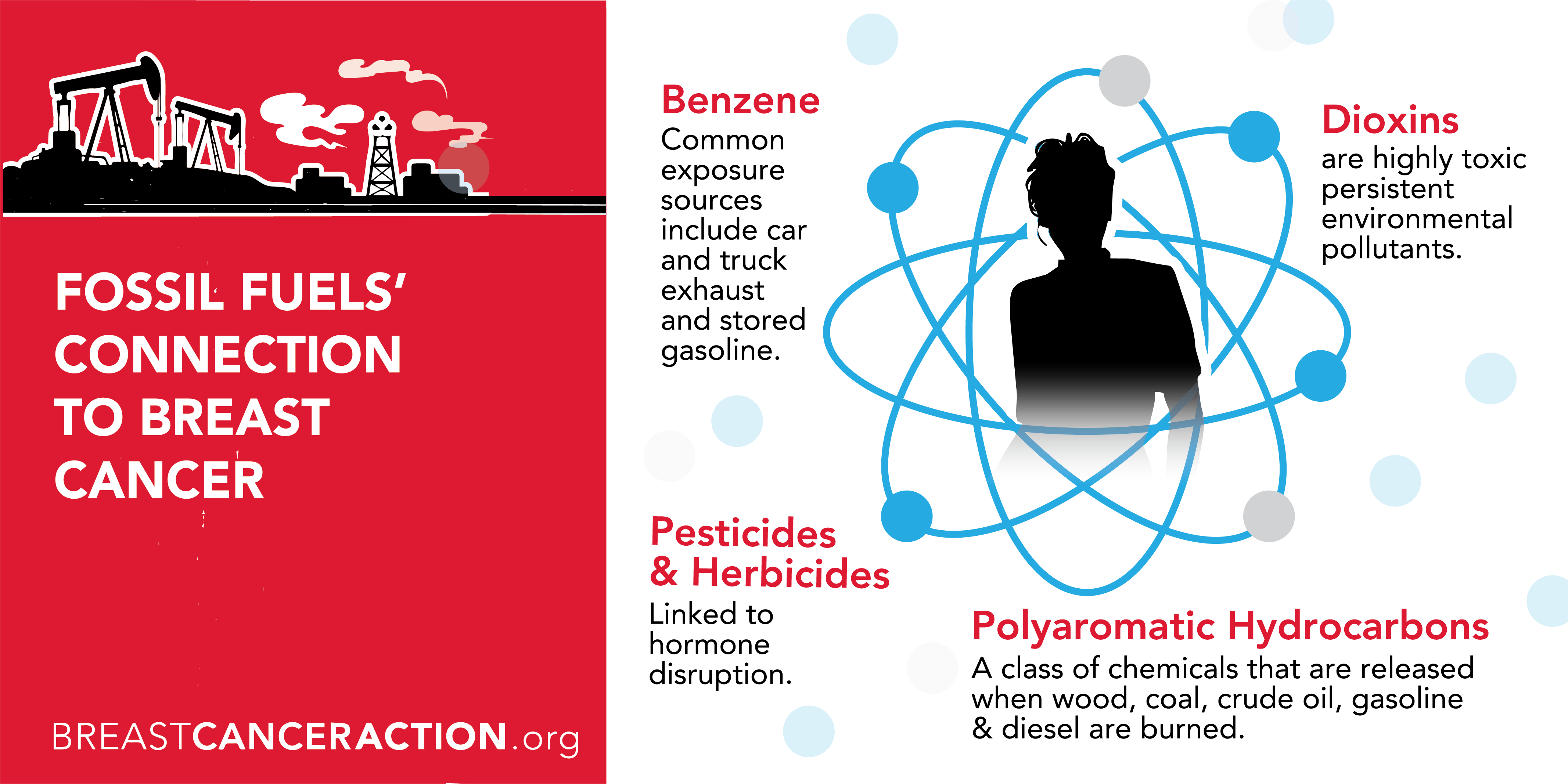

A growing body of evidence from experimental, body burden and ecological research indicates that there is a connection between environmental factors and breast cancer. Of the 42,000 chemicals in the market today, only 3,500 have been tested for safety.

The U.S. government has no adequate chemical regulation policy, which allows companies to manufacture and use chemicals without ever establishing their safety in humans. As the use of chemicals has risen in the U.S. and other industrialized countries, so have rates of breast and other cancers.

Key facts about the environment and breast cancer:

Just as environmental factors have been largely ignored as possible risk factors for breast cancer, so have the complex issues of social inequities – political, economic and racial injustices. The extent and type of toxins we’re exposed to often depends on where we live and work. Poorer communities — both urban and rural — shoulder an unequal share of the burden.

The social determinants of breast cancer likely contribute significantly to the development and mortality rate of the disease, and these involuntary factors are shown to be of greater impact on women of color and low-income women, since these populations are at greater risk for exposure to toxins and social injustice-related stresses.

Low-income women are also less likely to have access to healthy foods and quality healthcare. Compelling research and simple intuition tells us that true reduction of both breast cancer incidence and death from the disease requires a better understanding of how the complex tangle of the environmental and social factors, genetics and personal behavior results in different outcomes for different ethnic and economic groups.

Working to prevent breast cancer through lifestyle choices ignores the hard fact that we don’t all share equal access to those choices, and making healthy choices and trying to shop our way to prevention are not going to address the environmental links to the breast cancer epidemic. When we focus on the benefits of individual diet and exercise, we lose sight of the social justice issues that limit access to affordable healthy food and regular exercise for many in our society. If we are to address the root causes of this disease, it is imperative that we pursue the large-scale systemic changes that are necessary.

At BCAction, we strongly feel the best approaches are a combination of individual AND societal changes so that EVERYONE has the option of limiting their risk of getting breast cancer. To address and end the disease, we strive to eliminate involuntary exposures to harmful chemicals present in our daily lives that are making us sick. Our work is guided by the Precautionary Principle, an approach to public health that would protect consumers from suspected toxins by demanding ingredients be proven absolutely safe for humans before they reach market, not after people experience the results of contamination.

The Precautionary Principle is the common sense idea that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

The main components of the Precautionary Principle are:

Because the U.S. government has no adequate chemical regulation policy, when government does step in, it uses a “risk management” model which asks, “How much harm is allowable?” By contrast, the Precautionary Principle asks, “How little harm is possible?”

As we push for more and better data, we continue to demand that lawmakers and industry abide by the Precautionary Principle by acting now, on the basis of the weight of the evidence that already exists, to reduce and eliminate our exposure to chemicals we know or suspect cause breast cancer and other chronic diseases.

Such a principle was used in policy changes regarding the dangers of smoking, even though the precise mechanism of cancer causation has never been scientifically explained.

The Precautionary Principle of public health, which Breast Cancer Action advocates, calls for us to act based on the weight of the available evidence because waiting for “absolute proof” is killing us. In the absence of scientific consensus we need to adopt the highest standards: when in doubt, leave it out!

The challenge of breast cancer in an environmentally complex world requires innovative and collaborative approaches in addressing this issue politically and scientifically. Breast Cancer Action is committed to reducing all of our exposure to environmental factors associated with breast cancer and other cancers, and will work with other organizations similarly committed.

We can’t “run” away from breast cancer, no matter how much we exercise, no matter how many pink ribbon miles we walk. We need policies that protect all of us, regardless of our lifestyles or our ability to make the “right” purchases. No matter how much organic we eat, how quick we are to rid our kitchens of plastic, how much effort we put into safe cosmetics, we can’t just opt out of the toxins that come to us through our daily environment: through our water pipes and air, through the coatings on our store receipts and parking meter slips, and through our office environments and off-gassing carpets and paint, whatever natural products we’ve chosen in our own homes.

BCAction supports the reduction and ultimate elimination of exposure to identified environmental carcinogens, and advocates for legislation, regulation, research, and education necessary to accomplish this goal. All of this, these core principles, point to one clear need: systemic change. This means putting people before profits, whether it is drug development for patients or employing the Precautionary Principle for consumers. This means removing the burden of prevention from the individual and placing it squarely where it belongs: on our social and regulatory systems.