By Tibby Reas Hinderlie, Communications Officer

The San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) is the world’s largest annual breast cancer conference, and the stated intended audience is “an international audience of academic and private physicians and researchers.”

These doctors and researchers need a space where they can communicate complex ideas to each other quickly and thoroughly, yet the language used by these two groups when patients “are not in the room,” can reveal biases and the limits of a broken system, designed around profit and not for peoples’ needs.

Language matters. The words we use reflect ways of thinking that inform the way we do our work, and the priorities of the medical system under which we operate. Always outspoken and willing to speak truth to power, Breast Cancer Action has been highlighting many of these issues since our founding. Over the years, we’ve seen more and more people pick up the call for people-centered language, but there is still a long way to go.

Given the intended audience of medical professionals, the language used throughout SABCS can feel impenetrable for advocates without medical training. Filled with medical jargon and endless acronyms, those outside of the medical field like myself can have a hard time keeping up.

Given the intended audience of medical professionals, the language used throughout SABCS can feel impenetrable for advocates without medical training. Filled with medical jargon and endless acronyms, those outside of the medical field like myself can have a hard time keeping up.

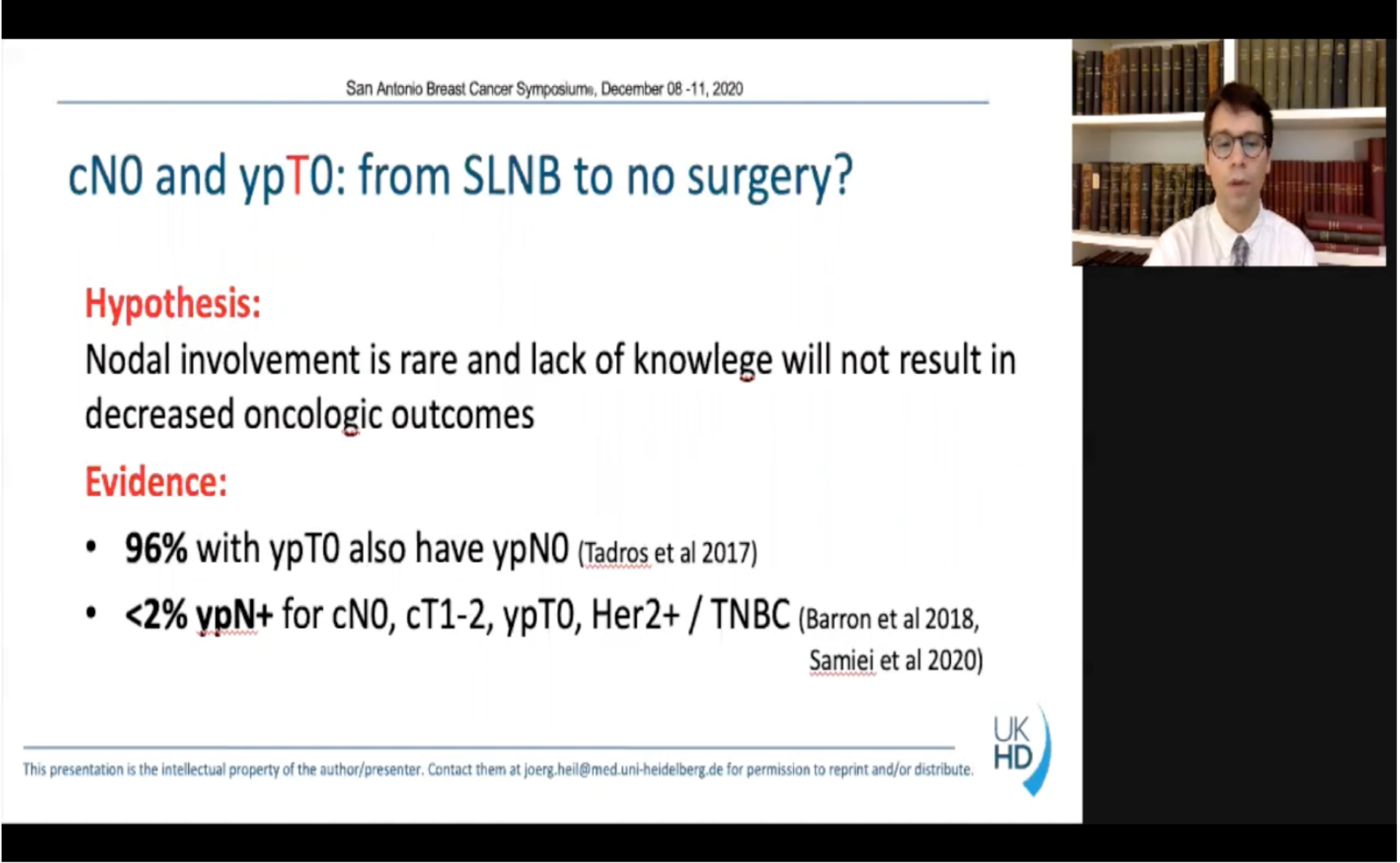

The examples of this are endless. Doctors use edema instead of swelling, ambulate instead of walk, and acronyms like ypN+ to mean “positive” lymph nodes, in other words that breast cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

The medical industry has a long history of using language purposefully to “protect” patients from the truth, but also of using language as a gatekeeper: to bolster the status as doctors as the keepers of knowledge, and to exclude others.

In “Witches, Midwives, and Nurses: A History of Women Healers,” Barbara Ehrenreich details how the medical establishment sought legitimacy through exclusion, solidifying the top spot of serving the ruling class under a burgeoning capitalist structure. She writes, “political and economic monopolization of medicine meant control over its institutional organizations, its theory and practice, its profits and prestige.” Women and lay healers were excluded through a formal barring from academic training, that is, from the newly institutionalized medical language: “The establishment of medicine as a profession, requiring university training, made it easy to bar women legally from practice. With few exceptions, the universities were closed to women (even to upper class women who could afford them), and licensing laws were established to prohibit all but university-trained doctors from practice.”

It is not by chance that Ehrenriech writes succinctly, “health care is the property of male professionals.”

Because of the pandemic, this was the first year without an in-person conference, and the first year that Patient Advocates were allowed to tune in to SABCS virtually, at no cost. Breast Cancer Action has been attending the conference as advocates for over 20 years, but with the new elimination of the cost to attend, it will be interesting to see if more advocates will participate in the future. And with the potential new influx of this audience, it will be interesting to see how, if it all, the language may change.

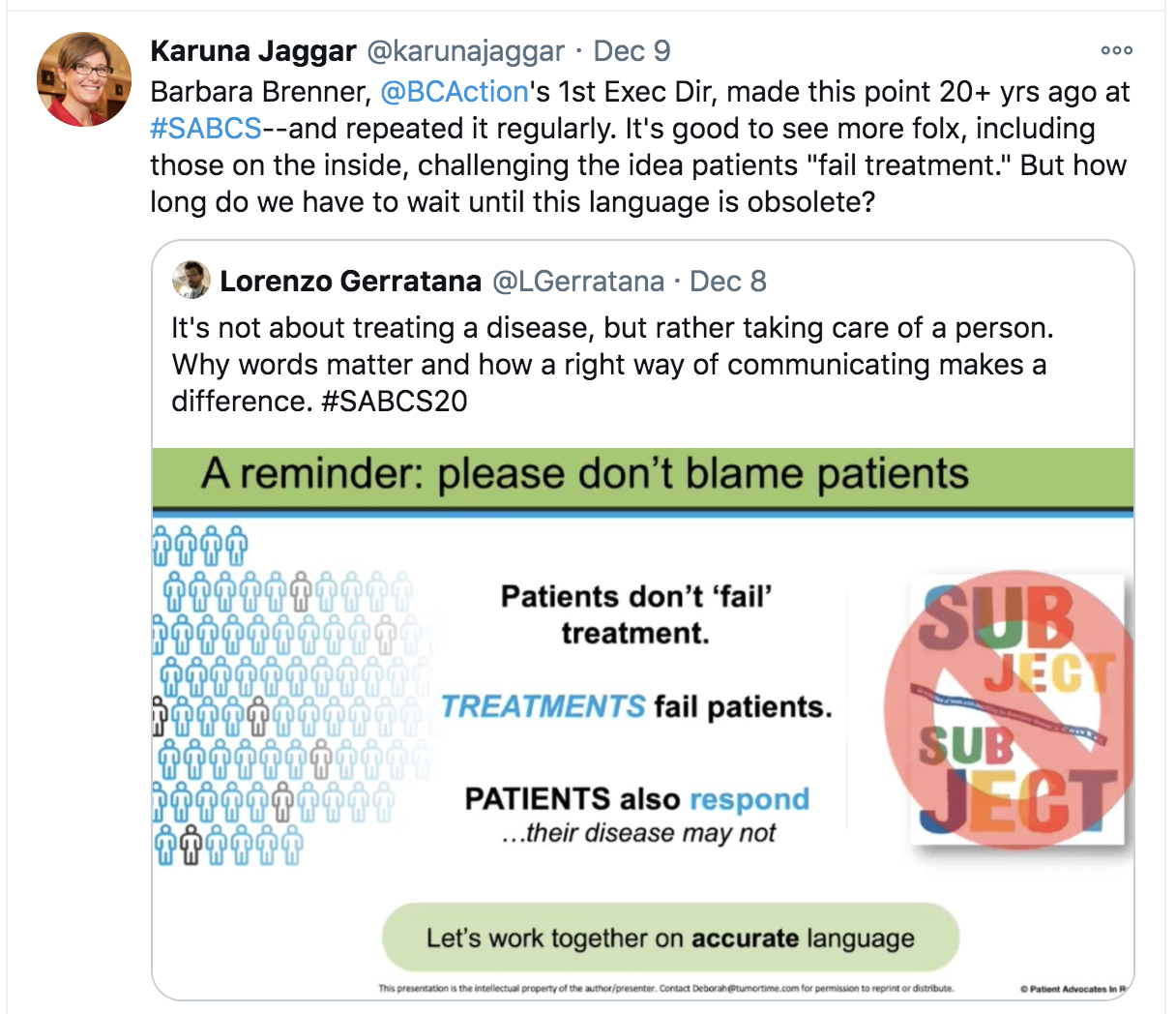

Barbara Brenner, Breast Cancer Action’s first executive director, was famous for calling the powerful to account at SABCS and proclaiming among other things, “Let me remind you that treatments fail patients, not the other way around.” So it was a pleasant surprise to see Dr. Lorenzo Gerratana call for this important shift in language—although we couldn’t help noting with some irony that he spoke for patients, rather than elevating their voices. In a tweet posted the first day of the conference, he posted a slide that reads “Patients don’t ‘fail treatment.’ Treatments fail patients. Patients also respond… their disease may not. Let’s work together on accurate language.”

Barbara Brenner, Breast Cancer Action’s first executive director, was famous for calling the powerful to account at SABCS and proclaiming among other things, “Let me remind you that treatments fail patients, not the other way around.” So it was a pleasant surprise to see Dr. Lorenzo Gerratana call for this important shift in language—although we couldn’t help noting with some irony that he spoke for patients, rather than elevating their voices. In a tweet posted the first day of the conference, he posted a slide that reads “Patients don’t ‘fail treatment.’ Treatments fail patients. Patients also respond… their disease may not. Let’s work together on accurate language.”

The language of who fails – the patient or the treatment – reflects who (or what) is being centered in the discussion. The goal of treatment is to help patients. When the treatment is centered instead of the patient, practitioners are missing the forest for the trees by framing the treatment as the object of interest, and the patients as the ones not doing their part.

While it is hopeful to see more people call for changes like these “from the belly of the beast” itself—that is, from within the medical establishment—but as our former Executive Director and SABCS Guest Writer Karuna Jaggar comments: “How long do we have to wait until this language is obsolete?”

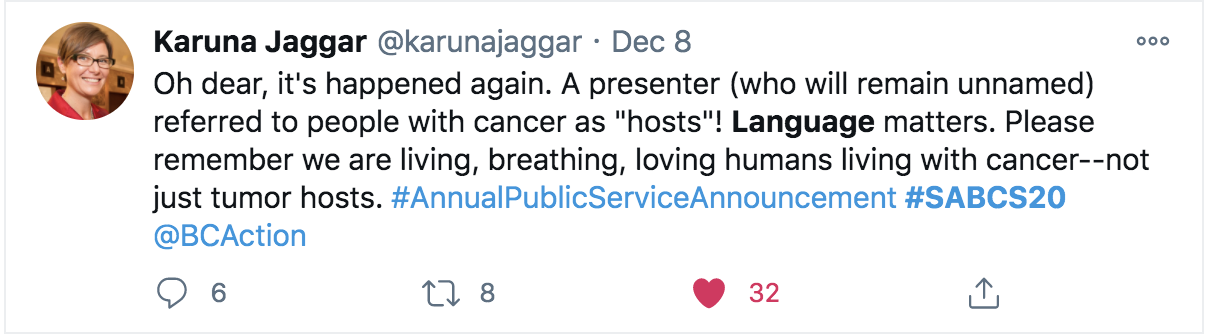

For the umpteenth year, Karuna Jaggar also caught another revealing moment where the humanity of patients was literally lost: when a presenter referred to cancer patients as hosts.

Hosts? Really? Even though people living with cancer may feel like our bodies have been invaded, it’s more like a hostile takeover than a hosted tea party.

As Karuna writes, “Please remember we are living, breathing, loving humans living with cancer—not just tumor hosts.”

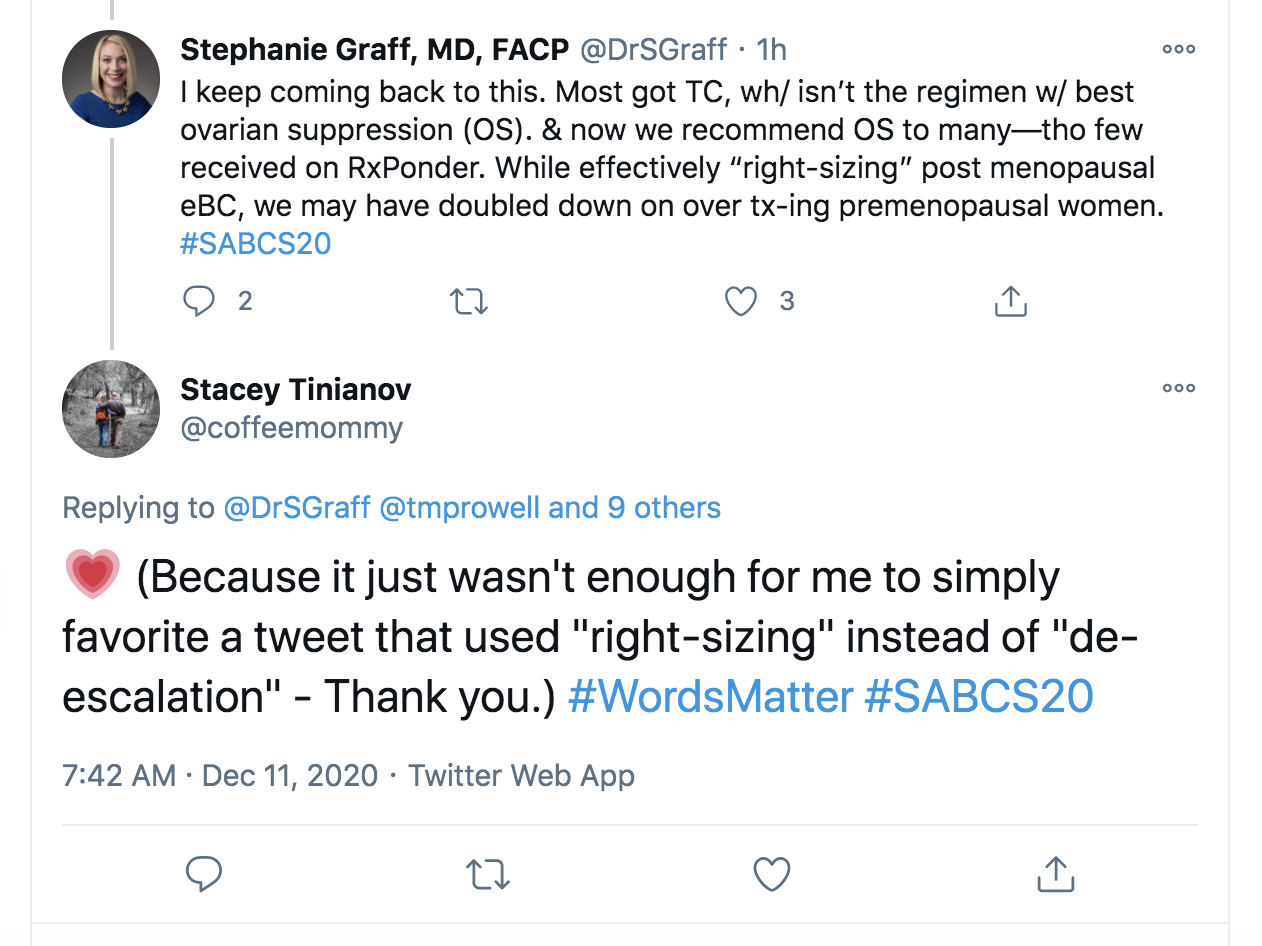

De-escalation continues to be a theme throughout SABCS, and this year included new protocols about safely omitting chemotherapy for some postmenopausal women, even with positive lymph nodes.

De-escalation continues to be a theme throughout SABCS, and this year included new protocols about safely omitting chemotherapy for some postmenopausal women, even with positive lymph nodes.

Some providers argue that instead of “de-escalation” we should talk about “right-sizing” but even that still masks the real problem: overtreatment. The framing of “right-sizing,” moves the focus from the treatment protocols as reflected in the phrase “de-escalation,” to the needs of the patient, but as Breast Cancer Action has been saying for years: we need to stop overtreating!

In our more-is-better culture and under a medical system which first researches the maximum tolerated dosage of a new drug (phase I trial) before determining if the drug works (phase II trial), overtreatment harms are common and they are severe.

While this call for new “right-size” language is more patient-centered, it conceals the real problem in this discussion which is not too little treatment, but too much.

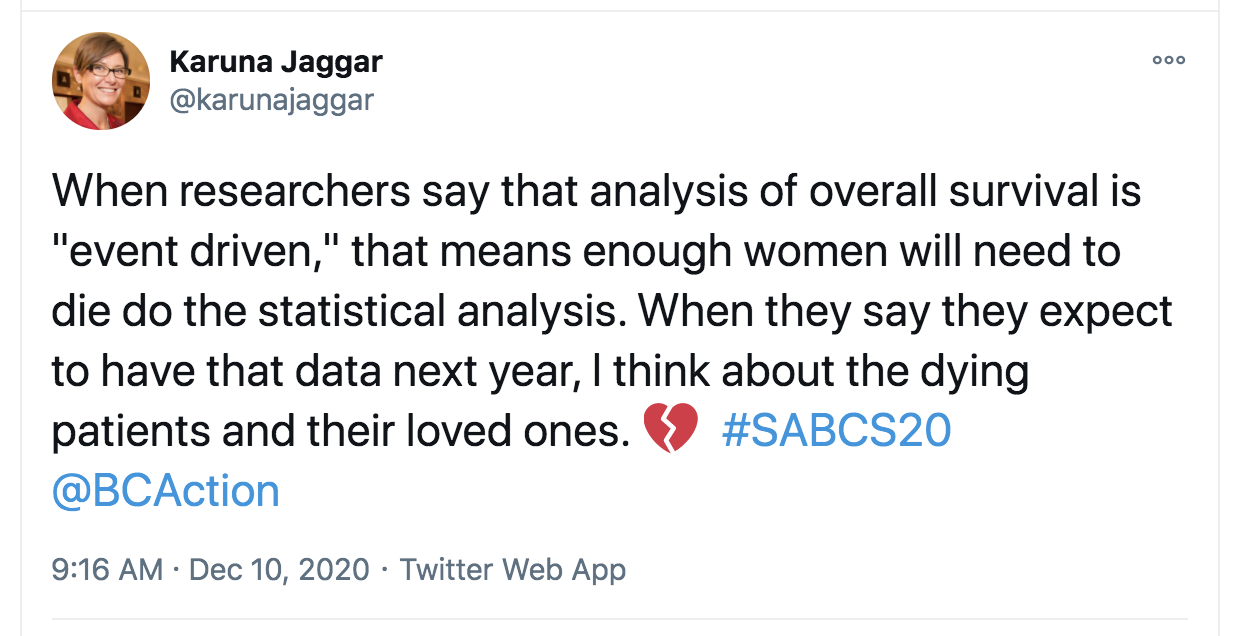

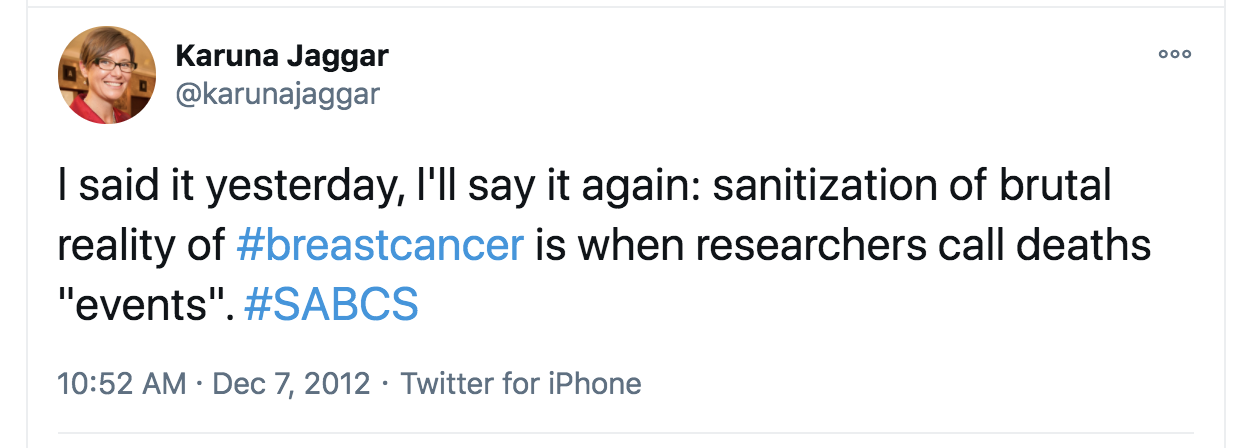

Another illuminating phrase is “events,” which is sometimes used as synonymously with deaths, but without the laying bare the true devastation we are grappling with when discussing breast cancer studies. Karuna Tweeted about this language choice throughout SABCS this year, just as she had done as far back as 2012.

Breast Cancer Action has long advocated that surrogate endpoints are not a replacement for overall survival data. The faster researchers can report on overall survival data, the worse the clinical trial participants are doing, because the awful reality is that reporting on overall survival means comparing rates of deaths. It’s actually good news for the people enrolled in the trial if it takes a long time to report overall survival data. But in the rush to bring new treatments to market, surrogate endpoints are faster and provide researchers with an intermediate indicator if the treatment is likely to work as hoped.

Sometimes, while explaining that there is not enough data to calculate overall survival rates, the researcher might say there have not yet been enough “events,” which is code for not enough people have died. This sanitation of death can feel like the study participants’ lives don’t matter and aren’t honored as they should be.

The framing of deaths as events also downplays that real lives are on the line: it frames the discussion around key points in the clinical trial, instead of the people who are meant to benefit from this research.

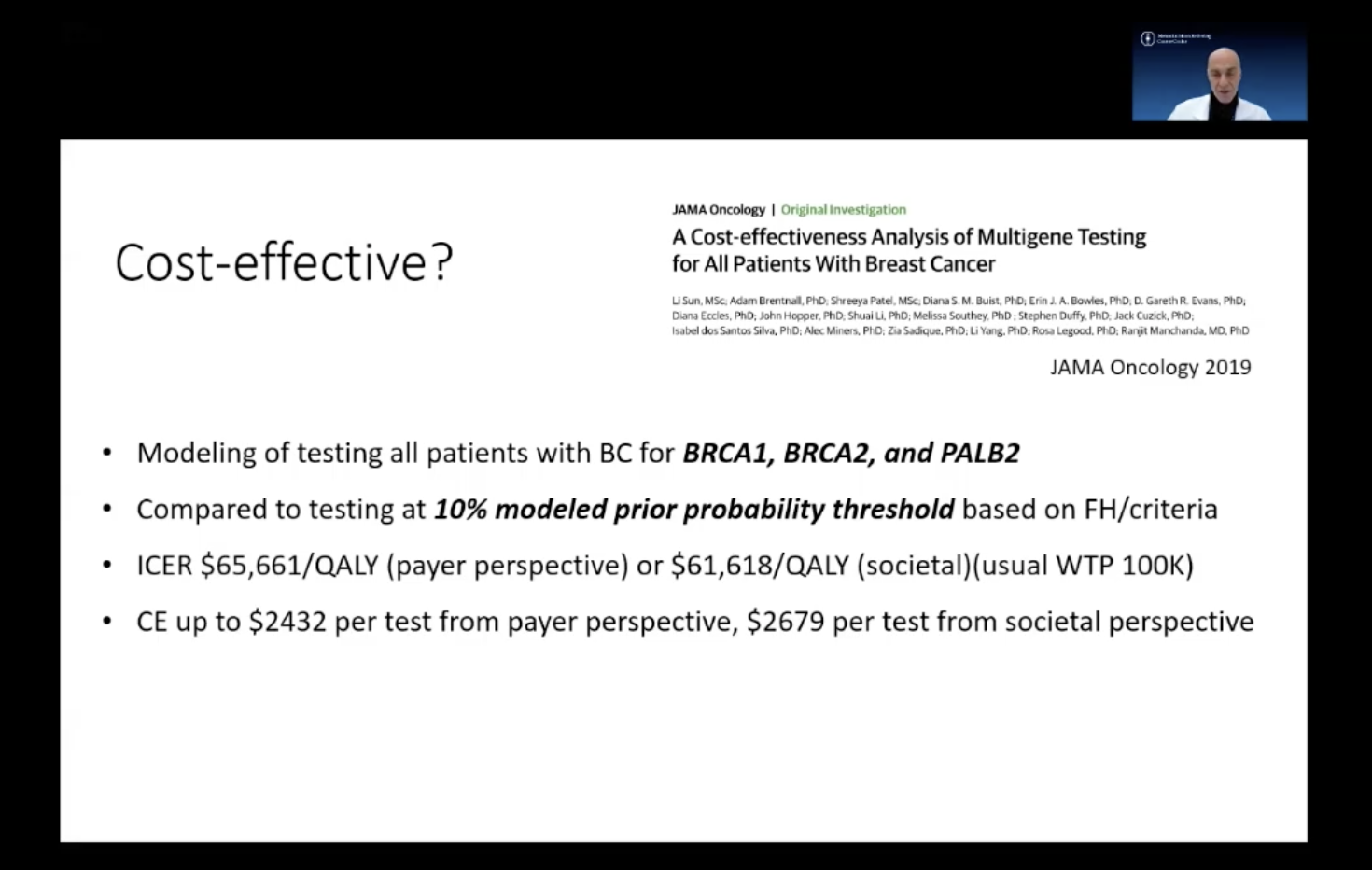

In Friday’s Debate, “All Breast Cancer Patients Should Have Germline Genetic Testing,” the participant representing the “For” argument, Mark Robson, MD, took into account a “Willingness To Pay,” economic model when analyzing whether or not testing all patients was cost-effective. “Willingness To Pay,” which was abbreviated on his slide WTP was described as “at a usual willingness to pay threshold of $100,000.”

In Friday’s Debate, “All Breast Cancer Patients Should Have Germline Genetic Testing,” the participant representing the “For” argument, Mark Robson, MD, took into account a “Willingness To Pay,” economic model when analyzing whether or not testing all patients was cost-effective. “Willingness To Pay,” which was abbreviated on his slide WTP was described as “at a usual willingness to pay threshold of $100,000.”

WTP is an economic modeling tool used to describe “the maximum price at or below which a consumer will definitely buy one unit of a product.”

I won’t do a deep-dive into health economics, nor Dr. Robson’s argument, but I want to take a moment to note how absurd it is that word “willingness” is being used in the context of breast cancer tests and treatments, many of which top $100,000 annually. Our health is not a consumer product, and using economic tools based on supply and demand to evaluate healthcare is deeply, fundamentally flawed.

Healthcare costs are the #1 cause of bankruptcy because we are infinitely willing to pay for our own lives. Supply and demand does not work because no one is willing to say “my life isn’t worth it,” or “your life isn’t worth it.” When it comes to the value of healthcare, i.e. the value of our lives, people will pay anything. They will mortgage their homes, go into bankruptcy, they will do anything to be “willing to pay” for treatment.

Willingness to pay is not the problem. Ability to pay is the problem.

Like many of the solutions we see to the breast cancer crisis, and like many policies under capitalism, the framing around willingness shifts the blame of accessing treatment to the individual, rather than reckoning with the flaws of for-profit system, including the fact that poverty is intentionally woven into the fabric of our society.

In a world where pharma and biotech companies can set their own prices not based on value but instead based on what the market can bear, we’ve seen prices rise exponentially and unsustainably. This betrays the fact that we cannot use standard economic framing when discussing our lives, and that the for-profit healthcare system is fundamentally flawed.

Breast Cancer Action has been at the forefront of advocating for patient-centered research, treatment, language, and practice for decades, and has long been pushing the medical establishment to see through this lens, whether or not patients are “in the room” to bear witness.

Under a capitalist, for-profit healthcare system, as patients and advocates we face both a history of exclusion from the medical industry as well as a focus on cost and profit that deprioritizes human life.

We know that many doctors and researchers are in the same boat with us: there’s no denying oncologists and their patients often have strong, unique bonds with their patients, and that doctors mourn the deaths of their patients just as they would that of a friend or family member. As doctors, researchers, activists, advocates, and patients who want to see fewer people die from breast cancer, we are all operating under a fundamentally broken healthcare system: one that objectifies people, necessitates self-protective measures to distance oneself from the heartbreak of death, and one that uses economic tools of cost-effectiveness when debating the value of treatment.

It will take all of us to rebuild the system in a way that centers the complexities of our lived experiences, our communal health, and our lives.