By Tibby Reas Hinderlie, Communications Officer

As a former yoga and meditation instructor I was immediately drawn to Dr. Patricia Ganz’s session on mindfulness at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS). I still maintain an active practice, and I felt joy and gratification to see the medical industry recognize the efficacy of a practice that many cultures have known to be beneficial for centuries.

But I am also cautious about interventions that shift the burden of mitigating the effects of breast cancer to the individual by imploring, “eat right, exercise, and spend time on the meditation cushion!” Outside of and in addition to meditation, there are a variety of systemic changes and policy solutions that could be implemented to produce broad reductions in psychosocial symptoms such as depression and anxiety.

How many people with breast cancer would experience a reduction in depressive symptoms if we had universal healthcare, and they were not facing oncoming poverty? How many patients would report an increase in positive moods if we had student debt relief, and they knew their incoming hospital bills wouldn’t be adding to an already insurmountable debt?

What kind of broad, nationwide reduction in anxiety could we produce if women across the country were told: “Your breast cancer was caused by a specific chemical exposure, produced by this specific corporation. This chemical will be banned, the contamination will be addressed, and the company will be held accountable, so that this never happens to another woman again?”

Dr. Ganz’s presentation on the benefits of mindfulness was titled, “Targeting depressive symptoms in younger breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation and survivorship education” (GS2-10). She gave an overview of the Pathways to Wellness study, a Phase III, multi-institution, randomized trial comparing two types of interventions, and showed how mindfulness was uniquely successful in treating depression in young people with breast cancer. The first intervention was a 6-week group program of Mindfulness Awareness Practices (MAPs), and the second was a 6-week group program of Survivorship Education (SE). In both study arms, site instructors delivered two-hour programs of structured content, and the two groups were compared to a control group on a wait list known as the wait list control (WLC).

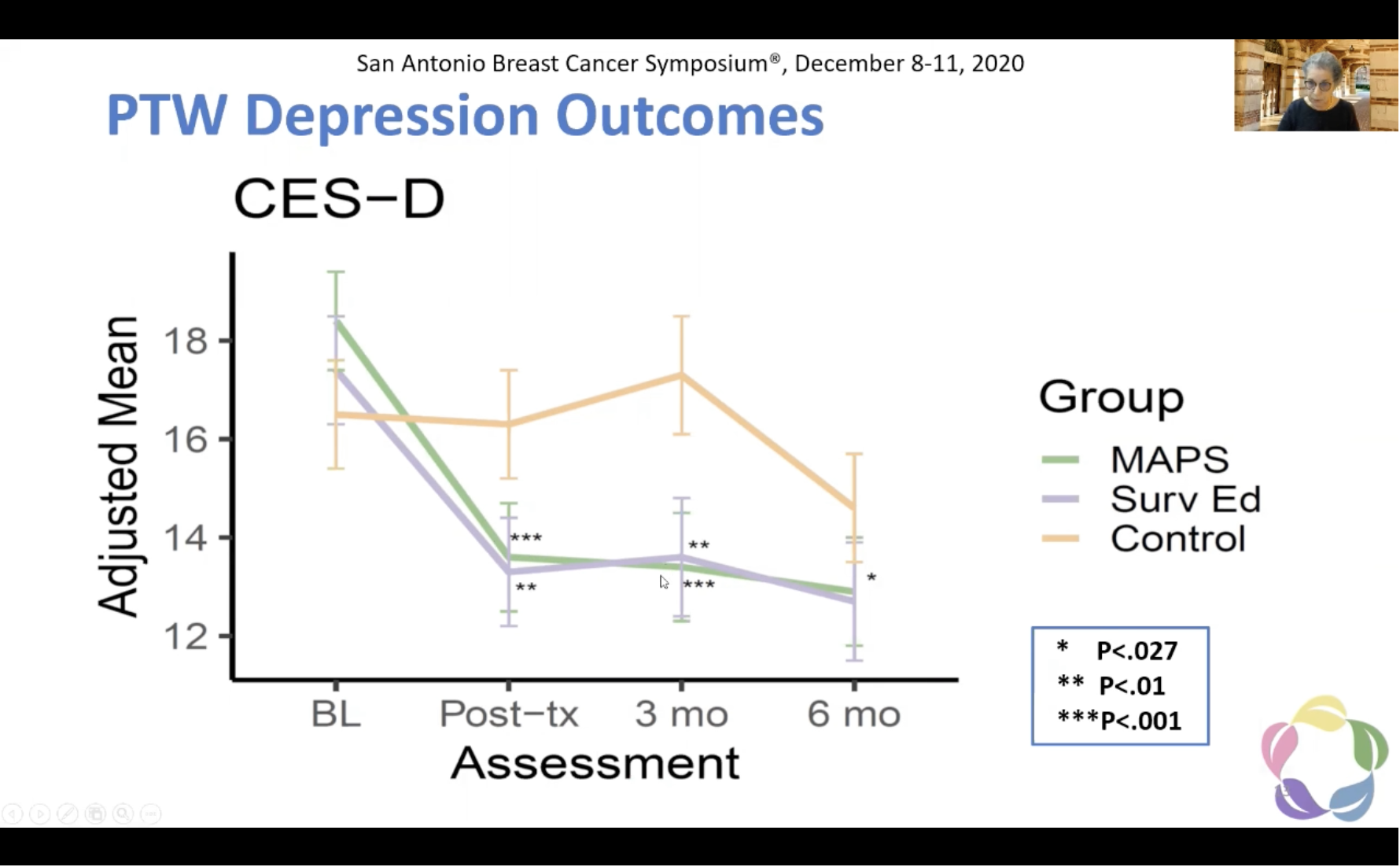

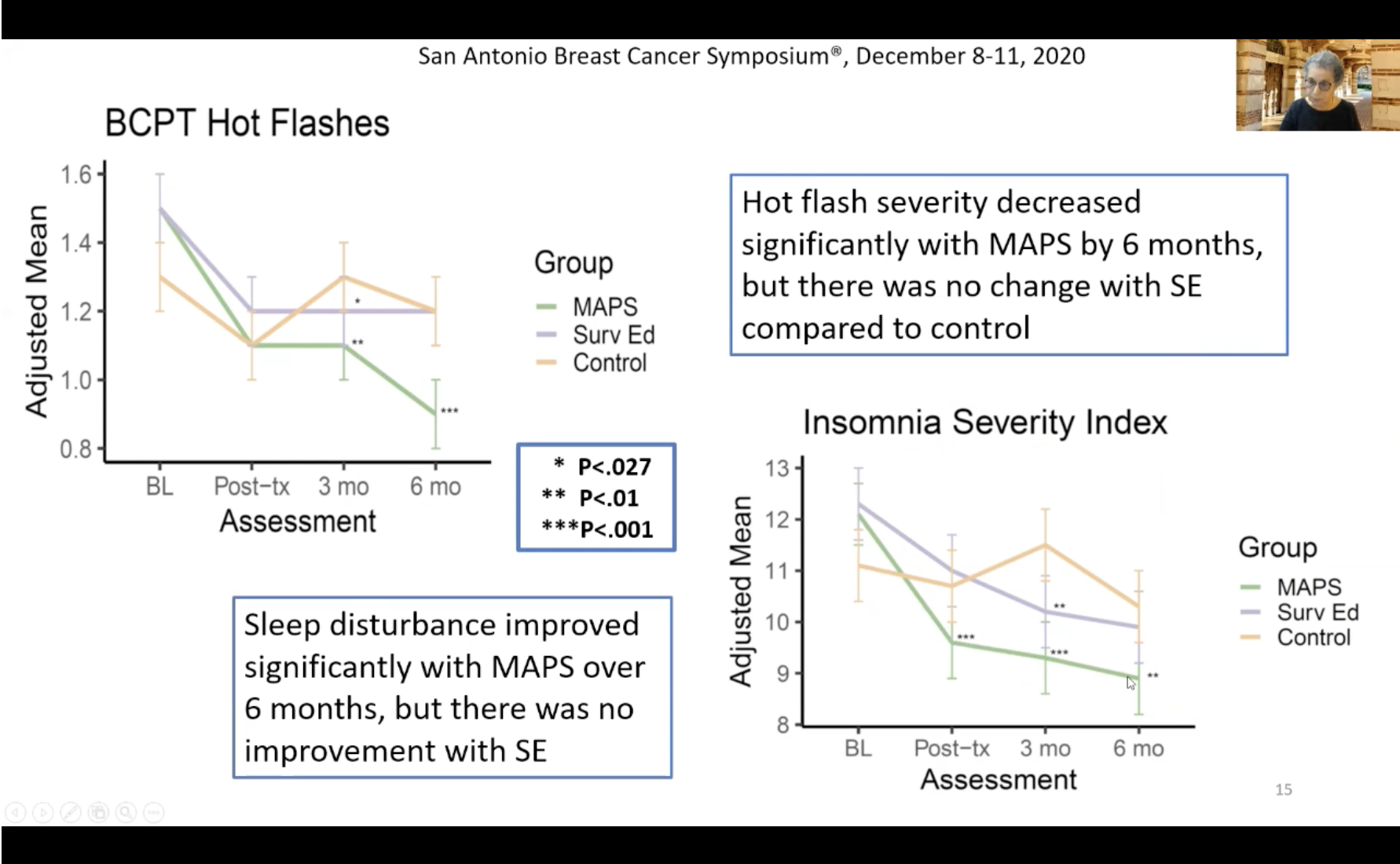

The results clearly demonstrated the benefits of meditation, which were both comparable to the benefits of survivorship education, but also went beyond the benefits derived by survivorship education alone. The primary endpoint evaluated was depressive symptoms, and secondary endpoints included four other behavioral symptoms: anxiety, fatigue, hot flashes, and insomnia.

Both the mindfulness group and the survivorship group saw a statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms. A significant reduction in anxiety was also observed in both groups. Interestingly, that was the extent of the similarities between the two groups. The correlation between the two groups diverged in regards to fatigue, hot flashes, and insomnia. Only the mindfulness awareness group experienced notable reductions in these three symptoms, which were not affected significantly by survivorship education.

So, does meditation work? Yes! But the premise of the question leaves something to be desired.

If our goal is to reduce the stress of and depression in people diagnosed with breast cancer, shouldn’t we pursue systemic and policy solutions that would reduce anxiety and depression: universal healthcare, paid family leave, guaranteed minimum income, and more? I look forward to the day when studies on the mental health and clinical benefits of these types of policy changes are presented at SABCS.