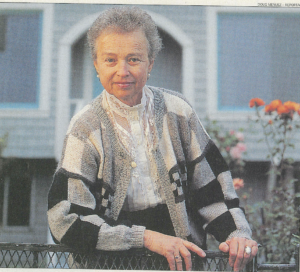

Elenore Pred, one of BCAction’s four original founders, was featured in a U.S. News & World Report series on The Most Notable Women of 1991. The profile, by Erica E. Goode, was published on August 26, 1991, just months before Elenore Pred died.

Elenore Pred, one of BCAction’s four original founders, was featured in a U.S. News & World Report series on The Most Notable Women of 1991. The profile, by Erica E. Goode, was published on August 26, 1991, just months before Elenore Pred died.

The toxic blue liquid that drips slowly into Elenore Pred’s chest is the same color as her Thai bedspread, the same royal blue as her sofa and her bathroom tiles and her favorite corduroy pants, the blue that has always been “her color”. It is one of the little ironies she finds in having breast cancer, in participating in its poisonous treatment. And Pred, who a year ago cofounded Breast Cancer Action, borrowing tactics from AIDs activists to draw attention to the illness that kills 44,000 women each year, thinking about this as she stares at the ceiling in her doctor’s office, as she anticipates the nausea and the vomiting and the “chemo mush brain” that will rob her of four precious workdays and send her crawling under her blue bedspread, her calico cat Patches watching from atop the computer.

On chemotherapy days, Elenore Pred’s public self retreats. Her smile, magnetic, puckish, incendiary, is in partial eclipse, and there is an unwilling hiatus in the stream of phone calls to Washington and Sacramento and Chicago, a grudging pause in her work on the walkathon and the theater benefit and the letter-writing campaign. For a few days reporters who call reach her answering machine, as do the women who phone from Michigan or Arizona or Maine seeking advice or simply solace from someone who is facing what they are facing – who has done something about it.

It is a bad trick to play on a woman like Elenore Pred, this regular surrender to the dripping blue liquid. Her activism is how she stays alive, much longer than the doctors predicted, fighting the malignant army that has crept through her body for a decade, its captains annexing her breast, then her lymph nodes, then slowly infiltrating her bones. It is how she diverts her anger, weaving meaning out of what could seem senseless, moving her inner struggle outward, drawing others in. “We are very angry, and we must stop treating this disease as a personal tragedy,” she tells them in speeches. And with each public appearance, each gesture of protest, she steals a few more weeks, a few more months, another year to watch her grandchildren grow and do her work and tend her garden and see movies. Another chance to say, “I’m not supposed to be here now,” and to laugh, because she is here, and intends to stay for a while.

Even as a child in Baltimore, hearing her parents argue about politics, talking about the labor movement and the Depression and dark nightmares brewing in Europe where their relatives lived, she could feel it, a silent exhortation to look beyond herself and try to make things better. God was a man named Roosevelt, his voice strong and reassuring on the radio. Sometimes her mother brought strangers home to dinner, like the black Catholic bishop who sat, tall and dignified, and talked about the country’s problems and what needed to be done.

As a teenager, Elenore began to forge her own politics, more left-wing than her parents’ solid Democratic stance. She argued and rebelled and moved on to her own life, to freshman chemistry – the course that persuaded her to major in psychology instead of premed – and later, to marriage and life as a housewife and mother in suburban Miami.

It was an illness that convinced her, at 25, that “life was too short to do anything but what I wanted to do.” A coincidence, perhaps, that it was her right breast, the breast she would later have removed, that became inflamed after the birth of her second child, the spreading infection causing the worst pain she had ever known. She nearly died, and one day, as her husband’s cousin held her hand during a visit, she saw a bright light and knew she was slipping away, and that the hand on hers was the only thing keeping her alive.

From then on, she began to spend more time working for the things she believed in. She marched against the atom bomb. She campaigned for John Kennedy, for civil rights, for an end to the Vietnam War. After her divorce in the late 1960s. Pred went further, renovating a farmhouse in Tennessee, working as a mail carrier, a photographer, an editor and finally a real-estate agent, starting a new life in what she thought would be a mecca for the women’s movement: San Francisco.

Self-help. “What if an army of one-breasted women descended on Congress…” It is a phrase written by a breast cancer victim that appeals to Pred in its outrage. She, too, is outraged. She will tell you the statistics: A few years ago breast cancer struck 1 in 11 women; now it strikes 1 in 9. She will tell you about women who have died, about their funerals, about how much she misses them. She will tell you that of the seven women in the self-help group she joined three years ago, only two are still alive. Yet for a long while she didn’t get angry. Not after the first doctor’s visit in 1979, when he sent her away, saying it was nothing, a piece of scar tissue, nothing to worry about. Not two years later, when she listened to the words “It’s malignant,” her stomach plunging. That night she went out to dinner with friends. “Losing a breast isn’t so bad. You don’t really need them,” one said, and Pred agreed, not realizing that it was not just a breast she would be fighting for.

Even in 1988, after the mastectomy and the chemotherapy, after the five-year mark when she was declared “cured”, after she joined the Peace Corps and one day, in Morocco, reached for her necklace and felt the lump on her collarbone, Pred did not get angry. In the next months, back in San Francisco, she did a lot of knitting. She was trying to heal herself, learning biofeedback, seeing an acupuncturist, submitting to the chemicals that she sometimes worried would kill her before the cancer did. But she was also preparing for death. Then her friend Alice died, and Ursula after her. Pred read an article that wrote off as hopeless breast cancer victims whose disease was advanced. And finally, she began to get angry: at the risk her daughters faced, at the lack of knowledge, at the complacency of scientists and government officials.

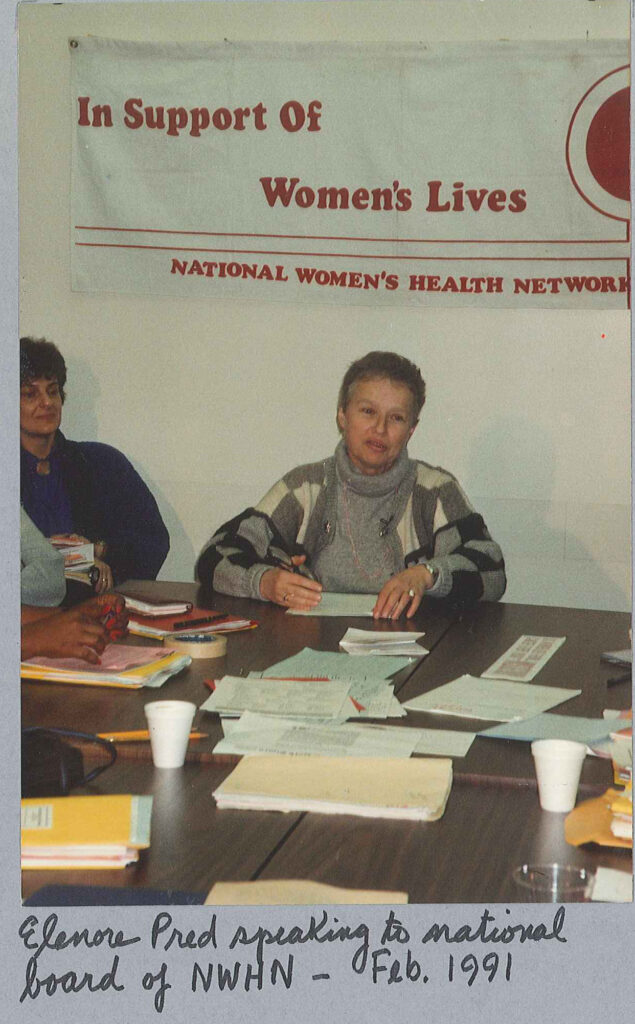

There were 12 of them at the first meeting, sitting on Elenore’s blue sofas. By the end of the evening, they had picked a name, elected officers, taken up a collection. “What are we going to do, march in the streets?” someone asked; Pred knew they would if they had to. On Mother’s Day this year, joining other groups, Breast Cancer Action marched on Sacramento, 1,000 women and husbands and children demanding more funding, faster progress toward a cure, more focus on prevention. A year of apprenticeship to AIDS activists has paid off: The media are taking notice, and so are government officials. There is a new awareness, and soon there may be change.

And so the days when Elenore Pred is captive to the toxic drug are the worst times. She cannot fight for the larger good but only for herself, enduring the private battle. She worries: What will happen when she can’t get out of the bathtub by herself? Who will write the mortgage checks? Who will feed Patches?

She is not afraid of death itself. She remembers when her father died, unexpectedly, a 75-year-old firebrand who fought the hospital nurses tooth and nail. At the end he grew calm and said, “I’m ready to go.” “Go where?” asked her brother-in-law. “Wherever I’m supposed to go,” her father replied. His words were a gift to her, a reassurance. When the drug levels subside and her body recovers, she will be back on the phone, back in the library, inspiring, organizing, planning. “I no longer think I can save the world,” she says, “but it is still important to me to make some difference before I die.”